Dask, Pandas, and GPUs: first steps

Summary

We’re building a distributed GPU Pandas dataframe out of cuDF and Dask Dataframe. This effort is young.

This post describes the current situation, our general approach, and gives examples of what does and doesn’t work today. We end with some notes on scaling performance.

You can also view the experiment in this post as a notebook.

And here is a table of results:

| Architecture | Time | Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|

| Single CPU Core | 3min 14s | 50 MB/s |

| Eight CPU Cores | 58s | 170 MB/s |

| Forty CPU Cores | 35s | 285 MB/s |

| One GPU | 11s | 900 MB/s |

| Eight GPUs | 5s | 2000 MB/s |

Building Blocks: cuDF and Dask

Building a distributed GPU-backed dataframe is a large endeavor. Fortunately we’re starting on a good foundation and can assemble much of this system from existing components:

-

The cuDF library aims to implement the Pandas API on the GPU. It gets good speedups on standard operations like reading CSV files, filtering and aggregating columns, joins, and so on.

import cudf # looks and feels like Pandas, but runs on the GPU df = cudf.read_csv('myfile.csv') df = df[df.name == 'Alice'] df.groupby('id').value.mean()cuDF is part of the growing RAPIDS initiative.

-

The Dask Dataframe library provides parallel algorithms around the Pandas API. It composes large operations like distributed groupbys or distributed joins from a task graph of many smaller single-node groupbys or joins accordingly (and many other operations).

import dask.dataframe as dd # looks and feels like Pandas, but runs in parallel df = dd.read_csv('myfile.*.csv') df = df[df.name == 'Alice'] df.groupby('id').value.mean().compute() -

The Dask distributed task scheduler provides general-purpose parallel execution given complex task graphs. It’s good for adding multi-node computing into an existing codebase.

Given these building blocks, our approach is to make the cuDF API close enough to Pandas that we can reuse the Dask Dataframe algorithms.

Benefits and Challenges to this approach

This approach has a few benefits:

-

We get to reuse the parallel algorithms found in Dask Dataframe originally designed for Pandas.

-

It consolidates the development effort within a single codebase so that future effort spent on CPU Dataframes benefits GPU Dataframes and vice versa. Maintenance costs are shared.

-

By building code that works equally with two DataFrame implementations (CPU and GPU) we establish conventions and protocols that will make it easier for other projects to do the same, either with these two Pandas-like libraries, or with future Pandas-like libraries.

This approach also aims to demonstrate that the ecosystem should support Pandas-like libraries, rather than just Pandas. For example, if (when?) the Arrow library develops a computational system then we’ll be in a better place to roll that in as well.

-

When doing any refactor we tend to clean up existing code.

For example, to make dask dataframe ready for a new GPU Parquet reader we end up refactoring and simplifying our Parquet I/O logic.

The approach also has some drawbacks. Namely, it places API pressure on cuDF to match Pandas so:

-

Slight differences in API now cause larger problems, such as these:

-

cuDF has some pressure on it to repeat what some believe to be mistakes in the Pandas API.

For example, cuDF today supports missing values arguably more sensibly than Pandas. Should cuDF have to revert to the old way of doing things just to match Pandas semantics? Dask Dataframe will probably need to be more flexible in order to handle evolution and small differences in semantics.

Alternatives

We could also write a new dask-dataframe-style project around cuDF that deviates from the Pandas/Dask Dataframe API. Until recently this has actually been the approach, and the dask-cudf project did exactly this. This was probably a good choice early on to get started and prototype things. The project was able to implement a wide range of functionality including groupby-aggregations, joins, and so on using dask delayed.

We’re redoing this now on top of dask dataframe though, which means that we’re losing some functionality that dask-cudf already had, but hopefully the functionality that we add now will be more stable and established on a firmer base.

Status Today

Today very little works, but what does is decently smooth.

Here is a simple example that reads some data from many CSV files, picks out a column, and does some aggregations.

from dask_cuda import LocalCUDACluster

import dask_cudf

from dask.distributed import Client

cluster = LocalCUDACluster() # runs on eight local GPUs

client = Client(cluster)

gdf = dask_cudf.read_csv('data/nyc/many/*.csv') # wrap around many CSV files

>>> gdf.passenger_count.sum().compute()

184464740

Also note, NYC Taxi ridership is significantly less than it was a few years ago

What I’m excited about in the example above

-

All of the infrastructure surrounding the cuDF code, like the cluster setup, diagnostics, JupyterLab environment, and so on, came for free, like any other new Dask project.

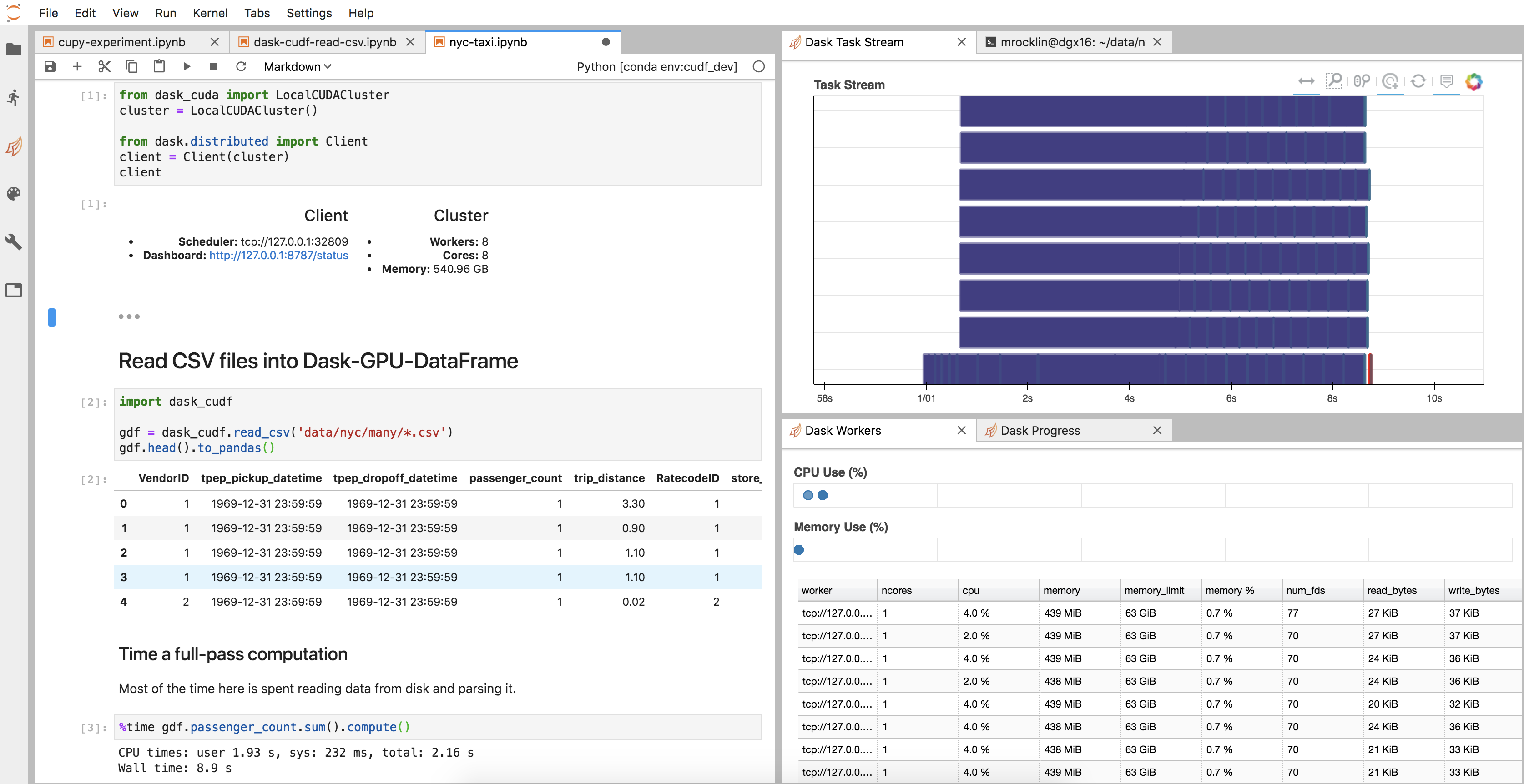

Here is an image of my JupyterLab setup

-

Our

dfobject is actually just a normal Dask Dataframe. We didn’t have to write new__repr__,__add__, or.sum()implementations, and probably many functions we didn’t think about work well today (though also many don’t). -

We’re tightly integrated and more connected to other systems. For example, if we wanted to convert our dask-cudf-dataframe to a dask-pandas-dataframe then we would just use the cuDF

to_pandasfunction:df = df.map_partitions(cudf.DataFrame.to_pandas)We don’t have to write anything special like a separate

.to_dask_dataframemethod or handle other special cases.Dask parallelism is orthogonal to the choice of CPU or GPU.

-

It’s easy to switch hardware. By avoiding separate

dask-cudfcode paths it’s easier to add cuDF to an existing Dask+Pandas codebase to run on GPUs, or to remove cuDF and use Pandas if we want our code to be runnable without GPUs.There are more examples of this in the scaling section below.

What’s wrong with the example above

In general the answer is many small things.

-

The

cudf.read_csvfunction doesn’t yet support reading chunks from a single CSV file, and so doesn’t work well with very large CSV files. We had to split our large CSV files into many smaller CSV files first with normal Dask+Pandas:import dask.dataframe as dd df = dd.read_csv('few-large/*.csv') .repartition(npartitions=100) .to_csv('many-small/*.csv', index=False)(See rapidsai/cudf #568)

-

Many operations that used to work in dask-cudf like groupby-aggregations and joins no longer work. We’re going to need to slightly modify many cuDF APIs over the next couple of months to more closely match their Pandas equivalents.

-

I ran the timing cell twice because it currently takes a few seconds to

import cudftoday. rapidsai/cudf #627 -

We had to make Dask Dataframe a bit more flexible and assume less about its constituent dataframes being exactly Pandas dataframes. (see dask/dask #4359 and dask/dask #4375 for examples). I suspect that there will by many more small changes like these necessary in the future.

These problems are representative of dozens more similar issues. They are all fixable and indeed, many are actively being fixed today by the good folks working on RAPIDS.

Near Term Schedule

The RAPIDS group is currently busy working to release 0.5, which includes some of the fixes necessary to run the example above, and also many unrelated stability improvements. This will probably keep them busy for a week or two during which I don’t expect to see much Dask + cuDF work going on other than planning.

After that, Dask parallelism support will be a top priority, so I look forward to seeing some rapid progress here.

Scaling Results

In my last post about combining Dask Array with CuPy, a GPU-accelerated Numpy, we saw impressive speedups from using many GPUs on a simple problem that manipulated some simple random data.

Dask Array + CuPy on Random Data

| Architecture | Time |

|---|---|

| Single CPU Core | 2hr 39min |

| Forty CPU Cores | 11min 30s |

| One GPU | 1 min 37s |

| Eight GPUs | 19s |

That exercise was easy to scale because it was almost entirely bound by the computation of creating random data.

Dask DataFrame + cuDF on CSV data

We did a similar study on the read_csv example above, which is bound mostly

by reading CSV data from disk and then parsing it. You can see a notebook

available

here. We

have similar (though less impressive) numbers to present.

| Architecture | Time | Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|

| Single CPU Core | 3min 14s | 50 MB/s |

| Eight CPU Cores | 58s | 170 MB/s |

| Forty CPU Cores | 35s | 285 MB/s |

| One GPU | 11s | 900 MB/s |

| Eight GPUs | 5s | 2000 MB/s |

The bandwidth numbers were computed by noting that the data was around 10 GB on disk

Analysis

First, I want to emphasize again that it’s easy to test a wide variety of architectures using this setup because of the Pandas API compatibility between all of the different projects. We’re seeing a wide range of performance (40x span) across a variety of different hardware with a wide range of cost points.

Second, note that this problem scales less well than our previous example with CuPy, both on CPU and GPU. I suspect that this is because this example is also bound by I/O and not just number-crunching. While the jump from single-CPU to single-GPU is large, the jump from single-CPU to many-CPU or single-GPU to many-GPU is not as large as we would have liked. For GPUs for example we got around a 2x speedup when we added 8x as many GPUs.

At first one might think that this is because we’re saturating disk read speeds. However two pieces of evidence go against that guess:

- NVIDIA folks familiar with my current hardware inform me that they’re able to get much higher I/O throughput when they’re careful

- The CPU scaling is similarly poor, despite the fact that it’s obviously not reaching full I/O bandwidth

Instead, it’s likely that we’re just not treating our disks and IO pipelines carefully.

We might consider working to think more carefully about data locality within a single machine. Alternatively, we might just choose to use a smaller machine, or many smaller machines. My team has been asking me to start playing with some cheaper systems than a DGX, I may experiment with those soon. It may be that for data-loading and pre-processing workloads the previous wisdom of “pack as much computation as you can into a single box” no longer holds (without us doing more work that is).

Come help!

If the work above sounds interesting to you then come help! There is a lot of low-hanging and high impact work to do.

If you’re interested in being paid to focus more on these topics, then consider applying for a job. NVIDIA’s RAPIDS team is looking to hire engineers for Dask development with GPUs and other data analytics library development projects.

blog comments powered by Disqus