Packages Considered Slightly Harmful

I originally presented this idea as a lightning talk at SciPy-2013. It is on youtube starting around 6:25

We start with the following principle

Principle: Refactor general code into a separate module/package

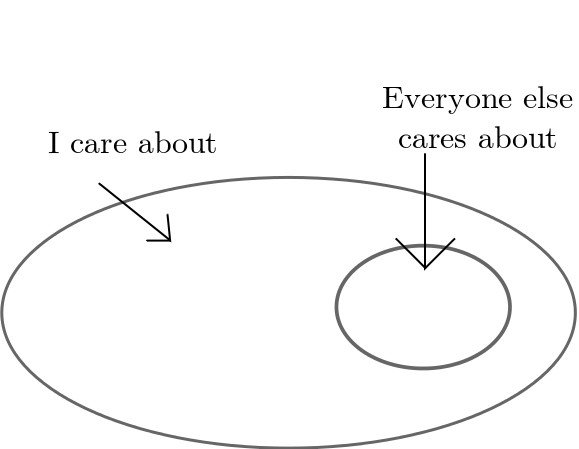

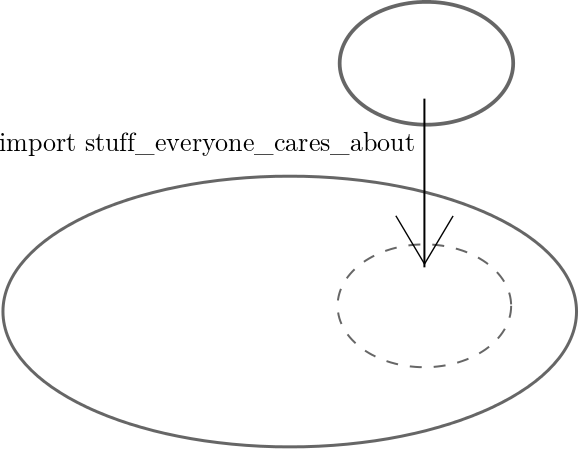

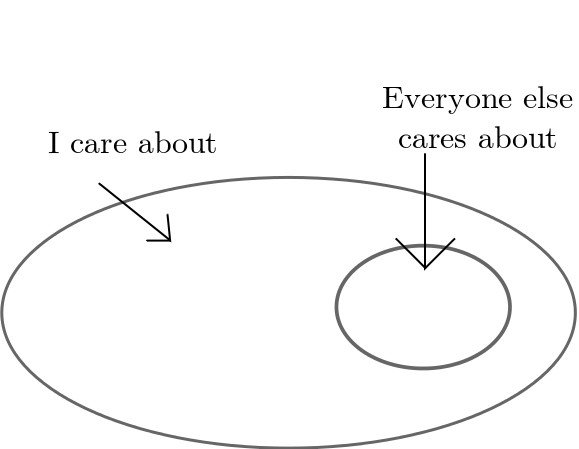

This principle is illustrated with the following pair of images (left: siloed code, right: open code)

| Before: General and specific code linked | After: Specific code imports general code |

|---|---|

|

|

Invariably packages contain code of varying general utility. Scientific codes often target specific applications (like genome sequencing of the fruit fly) but also contain some generally applicable routines (like fuzzy string matching). These general routines have great potential value to the broader community but are unfortunately sequestered within the special-case application code.

Problem: Packages unnecessarily tie together general code and application specific code.

Solution: Extract general components to separate packages. Import these packages into application specific code.

Absurdity

As with all good lightning talks, we take the idea to absurdity.

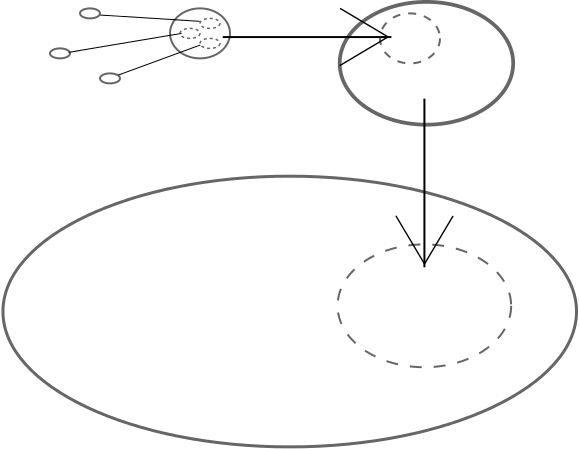

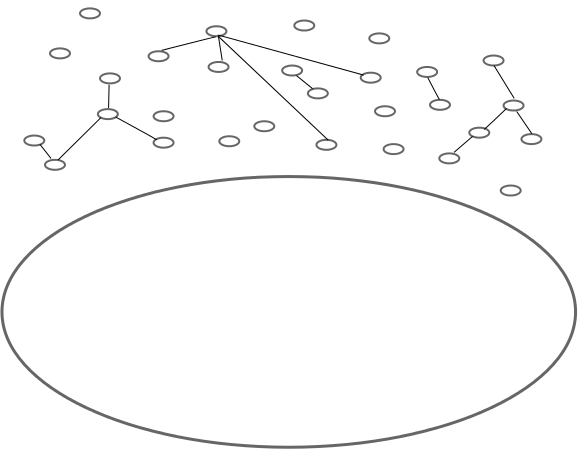

Invariably even the extracted general project will have components of more or less generality. We repeat our principle and separate the “general” package into its more general and less general components. We do this until no package contains components of varying generality. This process produces packages of boundless granularity.

| Separate super-general code from general code | Absurd separation to many tiny projects |

|---|---|

|

|

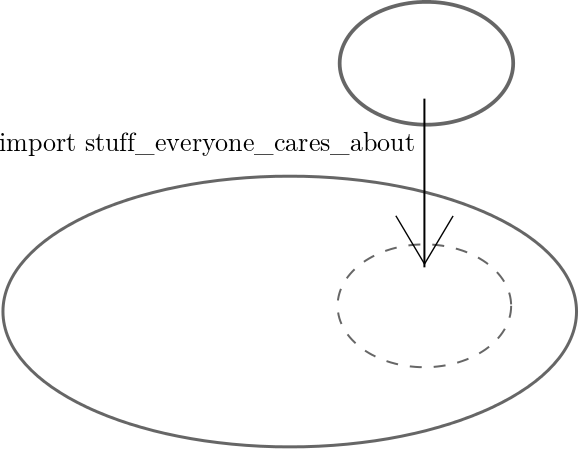

Intermediate projects become empty collections of imports. We remove them and find a sea of atomic packages with dependencies. Our application code becomes much smaller due to the sea of generally applicable code.

GroupBy

The talk then discussed groupby, a particular general function to group a collection by the action of a function. Groupby is discussed in more detail in a previous blog post.

names = ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', 'Dan', 'Edith', 'Frank']

assert groupby(len, names) == {3: ['Bob', 'Dan'],

5: ['Alice', 'Edith', 'Frank'],

7: ['Charlie']}

I love groupby. I implement it in most of my projects. A quick grep of my workspace directory shows that it is separately defined in six different projects.

Clearly this is sub-optimal. We should put the groupby function into a package. This raises the following difficult design decision:

In which package does groupby belong?

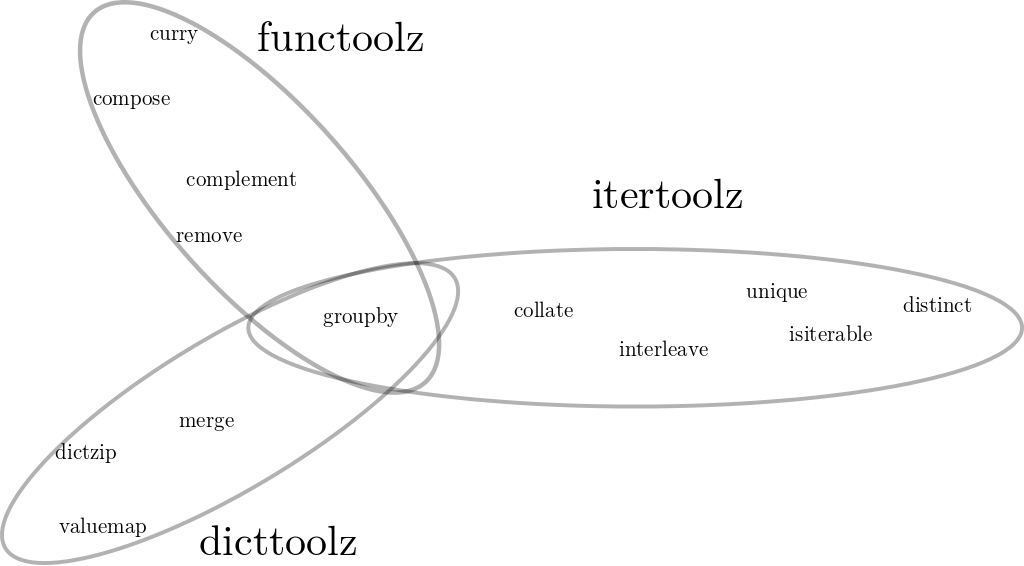

One could imagine placing it in a new itertoolz library because it consumes iterators. Or perhaps a dicttoolz because it produces a dict. Or perhaps a new functoolz because it is a higher order function like map or filter. Each of these utility libraries could use groupby. The principle to separate general code from specific code dictates that the ideal package must be the intersection of all larger packages.

The result is that groupby lives in its own project

from groupby import groupbyThis seems absurd.

Discussion

This talk generated significantly more discussion than my real talk. Here are some of the thoughts that came out of subsequent conversations with other SciPy developers. If you have thoughts please list them in the comments. I’m happy to modify this post to reflect your views.

Cross package testing is difficult

We often test interactions between different functions. If these functions are separated between different packages it’s not clear where the tests should go. We don’t have good tooling or practices for cross package testing.

Development across repositories is difficult

Developing new code with uncertain and dynamic interfaces is challenging. This challenge is compounded by the constant juggling of repository state. Cross developing different functions in many repositories imposes a significant mental load.

Package management has issues

I made the claim during my talk that managing dependencies is cheap. Many people brought up good issues with this and rightly so. Particularly non-Python dependencies and versioning both cause significant issues with dependency management.

My Thoughts

Dividing packages with boundless granularity clearly breaks current models of development. I do not recommend this development model literally for day-to-day work. Instead, I hope that people move somewhat in the direction of separating general code from specific code and using dependency managers more aggressively. Principles must be moderated with pragmatism.

Given that, I’m now going to talk about how one might resolve the issues above in an ideal world. I don’t think this is idle thinking. Programming communities constantly amaze me with their ability to overhaul their development models. The driving motivation for this work is

granular software ecosystems enable software evolution.

Separate source from tests

Placing source code and test code into separate projects specifies a clear interface and enables open competition. It demotes the original implementation and encourages alternative efforts.

Testing code need not be associated one-to-one with source code. Several different implementations can satisfy the same tests. We want to encourage several competing implementations; this competition enables growth and flexibility. Ease of competition is critical for a healthy and dynamic ecosystem.

For example, the testing function test_groupby clearly specifies the requirements for the groupby function. I satisfy this test with my implementation of groupby. Because these exist separately my implementation has no elevated status. Others may implement code to satisfy this test with equal voice. Elevating test suites to first class packages establishes clear interfaces and promotes competition

Source code does not depend on other source code; it depends on a consistent interface. Tests are used to specify this interface. It is not the case that scipy depends on numpy but rather that scipy depends on code that satisfies the numpy test suite. Accepting this separation enables alternative implementations (like DyND or Odin) to more easily displace NumPy. This evolution is critical to the evolution of existing scientific Python software to adapt to changing hardware.

Tooling can follow need

Many of the problems with granular dependencies involve existing tools (Python package managers, git.) These problems are surmountable. Recent experience with surmounting tool deficiencies is encouraging. git was developed to support a single large open source community when svn failed to scale. Frustrations with existing package managers have lead to new developments like conda.

If programmers adopt higher standards of package granularity then I am confident that tool developers and enthusiasts will move to support those practices.

Final Thoughts

The main point is this before and after pair of images.

| Before: General and specific code linked | After: Specific code imports general code |

|---|---|

|

|

The second point is that the challenges of software distribution have changed in recent years. The demands on the end user of organized software construction have been considerably lessened. This changes how we should approach software development, particularly within community codebases. We should consider how these practices affect the strength and adaptability of the ecosystem. This isn’t perfect yet but it seems to be improving. How do we want future development to look like to take advantage of these advancements?